Abstract:

The purpose of the project conducted by the team was to compare the energy efficiency of pure biodiesel compared to recycled biodiesel and test whether recycled biodiesel could replace other fuels in an effort to slow global warming. To do so, the team created methoxide, mixed it with the pure and recycled oils to create biodiesel, and then created a calorimeter in the i-lab to test its energy efficiency by burning the oil. Results showed that the pure biodiesel was more efficient than the recycled biodiesel, however, the difference was minimal and would not have an enormous effect in the long run. This means that it could be possible, with more tests, to use recycled biodiesel as the main source of fuel instead of regular fuels.

Information:

Topic Area: Thermochemistry

Question: Which biodiesel is more effective – pure biodiesel or recycled biodiesel?

Hypothesis: The pure biodiesel will be more efficient than the recycled biodiesel, since the recycled biodiesel will have more contaminants in it, but hopefully the difference will be minimal.

Timeline: 2.5 hours a week for 4 weeks

Introduction:

Every day, the state of the atmosphere continues to worsen and worsen as climate change runs unchecked around the world, with very few parties doing what they can to lower the impact humans have on the environment. Global warming is caused by the greenhouse effect – when heat is trapped by the atmosphere and radiates back onto Earth, warming it up. Certain things that people have done to help lessen the effects include using hybrid or electric vehicles, carpooling, and using solar power instead of fossil fuels. When considering how to best combat global warming, it is imperative to consider vehicles. Transportation accounted for 28 percent of the total CO2 emissions from the United States in 2016 (2). Therefore, one of the best ways to stop the warming trend is to use more efficient fuels for transportation. The usage of biodiesel instead of regular fuels could go a long way towards reducing pollution in the environment, if these fuels became the primary fuel used in engines, the effects could be extraordinary. Even when biodiesels are only used as part of the fuel for an engine, by being mixed with gasoline, emissions of greenhouse gasses are reduced by about 20 percent compared to pure gasoline (3). Therefore, understanding which biodiesels are the most efficient is very important. The efficiency of biodiesel is what the group will be researching. Previous studies show that biodiesel could reduce hydrocarbons by almost 30%, a significant change. The usage of biodiesel instead of regular fuels could go a long way towards reducing pollution in the environment, and this experiment could tell us how effective biodiesel will actually be if used in regular circumstances. It is unsure how efficient the process would actually be since the process involves finding used oils. The refining process would definitely be cleaner since it just involves the mixing of methoxide and not the long process refining factories put the oil through, meaning that there will automatically be a positive impact on the environment or at least a lowering of pollutants like sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxide. For the experiment conducted by the team, we will be creating biodiesel and comparing its energy efficiency with that of other fuels taken from the kitchen to find the most efficient fuel as a possible replacement for fuels that cause more harm to the environment. In regards to the different fuels that will be tested, we believe that the pure vegetable oil taken from the store will be a more efficient fuel because it is less contaminated by pollutants that the home-made refining process could not remove from the biodiesel, however, the difference will be minimal.

Materials:

Methoxide:

- Methanol (liquid)

- Potassium Hydroxide (solid)

- Graduated cylinders

- Weighing scale

- Plastic bottle with lid

Biodiesel:

- Mason jar

- Methoxide

- Oil (pure and recycled)

Titration:

- Buret

- Glass flasks

- Buret Stand

- Indicator (phenolphthalein)

- pH paper

- Oil (recycled or pure)

- Methoxide

Calorimeter

- Metal can, both ends open

- Smaller metal can, one end open

- 2 temperature resistant rods (glass or metal)

- Handheld drill

Energy Tests:

- Calorimeter

- Biodiesels

- Logger pro software

- Vernier thermometer

- Laptop

- Disposable aluminum tea light holder

- Flask or beaker

- Baking soda

- Distilled water

Procedure:

Making the Methoxide

In order to make our methoxide, 40 mL of methanol was measured out under the fume hood. Then, 1.7 g potassium hydroxide was weighed on a scale, quickly so that it absorbed as little moisture as possible from the atmosphere. The potassium hydroxide and methanol were then mixed in a plastic bottle and shaken for approximately ten minutes, stopping once to open the lid slightly and let the hot air released by the reaction out.

Performing the Titration

The materials for the titration, such as the buret, stand, indicator, oil, and methoxide were set up first. Then, 1 g of 0.1 M potassium hydroxide was dissolved in 1 L of water and poured into the buret until the buret was full, about 50 mL, and the rest was left for the other trials. Twenty mL of isopropyl alcohol was measured out in a beaker then, and then 3 drops of the indicator, phenolphthalein, was added. One mL of oil was added to the alcohol and indicator and mixed. The buret with the potassium hydroxide solution and the flask were then set up on a stand. The solution was then dripped into the flask of oil mixture until the liquid turned a light shade of pink, a color created by the indicator that indicates neutralization in the solution. The difference between the initial volume and the final volume of the reference solution was then found, and the entire process was repeated thrice. Then, the average of the three differences was found and then used to find the ratio of potassium hydroxide to methanol in the methoxide for the biodiesel. To throw away the mixtures, pH paper was used to check the acidity. If the mixtures had a pH between 5-8, then it could be thrown away in the sink, otherwise, it was taken into a separate container to be disposed of elsewhere with inorganic waste.

Making the Biodiesel

Two hundred mL of our chosen oil, recycled kitchen oil or olive oil, was put in the jar of methoxide then, and shaken together for approximately ten minutes. It was left to sit for the rest of the day, and next class, the glycerin, at thicker, brown layer with a higher density than the oil was drained from the bottom of the container until just the biodiesel was left. Using a spray bottle, water was sprayed into the container and filtered out with the contaminants in the biodiesel.

Making the Calorimeter

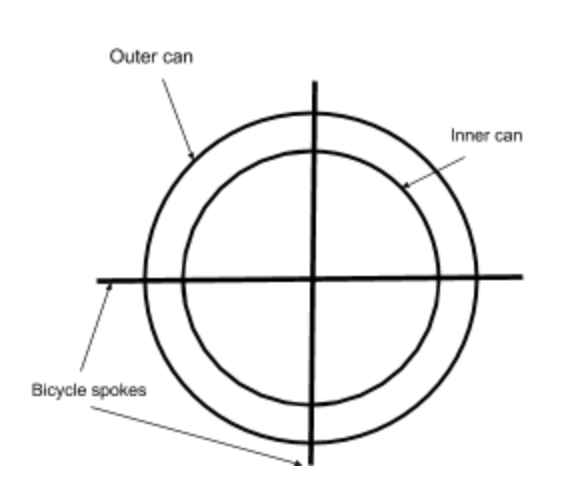

The calorimeter was created using two metal soda cans, one being wider than the other (1 Izzy can, 1 Diet Coke can). Four holes were poked in each can, evenly spaced near one end, top or bottom, using a handheld drill with a thin drill bit from the I-lab. Two bicycle spokes, the temperature resistant rods, were then put through both cans so that the thinner can was suspended within the wider one (Fig. 1).

How to test Energy Efficiency

The energy efficiency of the biodiesels was tested using the calorimeter. The inner can was filled with water at room temperature, around 20℃, the exact temperature of which was recorded using a Vernier thermometer and Logger Pro software on our computer. Then, the entire calorimeter was suspended using a ring and stand. Under this was an aluminum tea light holder with 10 ml of biodiesel in it (Fig. 2). Paper towel, the same type used in bathrooms for drying hands off, was then dipped in the oil, and once it absorbed the oil, was lit on fire with a lighter. While the fire was burning, a temperature probe continuously measured the temperature of the water until the data collection was complete (3 minutes), even though the fire usually burned for longer. Using the difference between the two water temperatures, the amount of energy released by burning the oil could be calculated in calories. The fire was then put out using baking soda, some of the fires extinguished without needing help. This worked, though the amount of oil did have to be decreased to 5 mL since the fire was getting rather big with 10 mL of oil.

How to Perform the Calculations:

Caloric value: calories = volume of water (in mL) x the temperature change (in Celsius)

Energy in joules= water mass x heat capacity of water x temperature change

mL of methanol = 0.2 x L of oil used to make the biodiesel x 1000

Grams of KOH = (8.5 g KOH + reference solution average) x L of oil used to make the biodiesel

Data:

The experiment conducted suggested that pure biodiesel is slightly more effective than recycled biodiesel, releasing about 2x more energy in joules than the recycled biodiesel and about 100 more calories. The average amount of calories of the olive oil biodiesel and the kitchen oil biodiesel were 1483.3 and 1353.3 respectively and the average amount of joules were 6,200.3 and 5656.9 Joules respectively. The temperature of the water increased anywhere from 6.6 ℃ for the recycled biodiesel to 18.9 ℃ for the pure biodiesel; 7.8 ℃ for the pure biodiesel and 20.1 ℃ for the recycled biodiesel (Figs. 4-5). In addition, by dividing the energy released by the olive oil biodiesel by that of the kitchen oil biodiesel, in both cases, the olive oil biodiesel released about 1.1 times more energy.

Data Table:

Table 1: All data logged during the experiment for the pure biodiesel and recycled biodiesel

100 mL of water

5 mL oil except for Olive Oil Trials 1 + 2, those had 10 mL

Graphs:

Graph 1: Temperature changes for the different biodiesel tests (go to table 1 for which color is which test)

Analysis:

The experiment conducted suggested that pure biodiesel is slightly more effective than recycled biodiesel, releasing about 1.1x more energy in joules than the recycled biodiesel and about 100 more calories. The temperature of the water increased anywhere from 6.6 ℃ for the recycled biodiesel to 18.9 ℃ for the pure biodiesel; 7.8 ℃ for the pure biodiesel and 20.1 ℃ for the recycled biodiesel. The temperature differences varied in some cases, but overall reflected that pure biodiesel is more efficient than recycled biodiesel. There were a few possible results that could have been made, the first of which is that the kitchen oil was not first purified and then turned into biodiesel. This could have resulted in the recycled biodiesel being less efficient, since some of the pollutants were unable to be filtered out before the creation of biodiesel, resulting in a bottle of separate waste. Another factor could be that for the first two tests on the pure biodiesel, 10 mL of oil was used instead of 5 mL like on the rest of the tests, and this could have shown the pure biodiesel to be more efficient than it actually is. On the data table, the one test where 10mL oil was not used is the one test that reflects a significantly lower amount of energy released compared to the two tests with 10 mL of oil. Not too many tests were conducted – just three for each oil, and this could mean that the actual average of the results, upon performing more tests, could be significantly different and reflect a different conclusion. It was concluded that pure biodiesel is more efficient than recycled biodiesel, however, the difference as seen was negligible, an only 1.1x difference in joules, in some cases and comparisons and could mean that the change to recycled biodiesel could be possible in order to help the environment. If there was more time to continue the project, more tests would be conducted on the biodiesels, easily ten or more burnings, in order to get a more accurate picture of the situation. The data that was collected, though, shows that though there is a difference between the efficiencies of pure and recycled biodiesel, the difference is small enough that with more tests, it could be proven that the two are of the same efficiency and that recycled biodiesel could be used in place of fuels that have to be created in factories that let out clouds of pollutants such as sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxide. The effect this could have on the environment is huge – if biodiesel is put into proper use, studies have shown that hydrocarbons in the atmosphere could reduce by almost 30%. The effect this could have on the environment and the rate of global warming is huge, and more tests could do a lot towards pushing the case for a change to recycled biodiesel.

Daily Reflections

2/11/19:

Today, Sarah and I plan to plot out a timeline for our experiment and start on writing our project introductions. We also want to finish reading through the BioDiesel link from the University of Chicago for the biodiesel project to get a better understanding of the experiment. As the research went on, we had the idea to make different biodiesels and compare their efficiencies based on what oils were used to make them. We decided against that since one or two store-bought oils would be enough.

We also devoted time to working on the timeline and plotted out a timeline for the experiment going all the way until the STEM Fair, and after mapping out our procedure and materials for the biodiesel and methoxide portion of the experiment, started research for the calorimetry part, or the energy efficiency. The idea centers around burning food near a beaker of water and then, as the energy released flows into the water, measuring the temperature change and converting the temperature change into energy released. This is done with real foods to find calorie intake.

Next class, we plan on creating our methoxide in order to start the creation of biodiesel. Methoxide making should take an entire class.

2/13/19:

Today, Sarah and I are going to make methoxide. I got oil from the kitchen and a jar from my house, so we have all the materials. We plan to make a large amount of methoxide, and then the next class perform a titration to figure out exactly how much we will need for the biodiesel. This way, we can make more than one batch if necessary.

We ended up finishing the creation of our methoxide, on schedule to our timeline. It was rather nerve-wracking since all the websites said that the two are very toxic, and we wore gloves and goggles. The reaction was fun though since the bottle heated up with the energy released from the reaction used to make methoxide. We didn’t use the jar that I brought and used a plastic bottle from the chemistry room. Since we had extra time, we decided to perform the titration, but more research told us that oil didn’t have a pH, so we had to do more research and talk to Jeremy. Things changed, however, when he said that the best thing to do would be to follow protocol and make a batch of biodiesel with clean vegetable oil in order to see about how much is necessary. The plan changed, then, and we ended up making one batch of biodiesel with 200 mL Extra Virgin Olive Oil and methoxide. We mixed the two, shook for a really long time, and then let it sit until the next class.

Next class, we plan on performing a titration on our kitchen oil to figure out how much methoxide will be needed, and make more methoxide for our new biodiesel. The experiment might change, however, to measure the effectiveness of pure oil biodiesel, kitchen oil biodiesel, and pure oil.

2/15/19:

Sarah and I plan on filtering the glycerin out of our batch of biodiesel from last time and cleaning it. On the walk to school, we also had the idea of using ratios to figure out how much methoxide is needed for our next batch with the kitchen oil instead of a titration. The idea is to measure the pH of the old olive oil, and how much methoxide was needed, and then find the pH of the kitchen oil, and use ratios to find how much methoxide will be needed. I also brought a can, though it is if IZZE so we’ll probably have to cut it down and get another can from Jeremy. Hopefully, with this information, we can make a new batch of biodiesel and methoxide using the kitchen oil, and if not, at least methoxide.

During the experimentation, we found that the second time around, we made the methoxide much quicker and in a way more efficient manner. We also made 80 mL instead of 40 mL because we will need a lot of methoxides. We also put the biodiesel in a new container so it would be easier to drain the glycerin, and gave the jar a quick wash. We had some trouble with the indicator since the internet told us that phenol red would be best, but more research told us that phenolphthalein would work too since there was no phenol red in the lab. In the setting up, however, the buret we grabbed was broken, and wouldn’t stop dripping methoxide. This resulted in Sarah getting some on her bare hands, and after that, the class was kind of chaotic. We had to clean up the methoxide and put it into a new buret, but then it turned out that you can’t titrate an oil because it’s not a pure liquid, so the titration mess was for nothing. We used pH to figure out the range in which they lie. Then, we had to clean everything up and decided to finish purifying the biodiesel in the process. I have to say, at least it was a learning experience.

Next time, we hope to do more pH measurements, make more methoxide, and make the batch of kitchen oil biodiesel. Along with this, we hope to maybe start on the calorimeter by getting rid of the contents of my can.

2/25/19:

Sarah and I, looking at our timeline, know that this week we need to finish making the rest of our biodiesel, especially the stuff with the kitchen oil so that we can begin to test their different efficiencies using the calorimeter. We also need to make the calorimeter, which is going to take time since we will need to go to the i-lab after school to cut our soda cans, and we don’t have too much time after school.

Measuring the pH of the oil was a little troubling for us since it seemed as though the papers only got wet, or stayed the same color. If they were the same pH things would be much easier, but we weren’t sure, so we talked to Jeremy. We ended up deciding to go down a different path, and start on the calorimeter. We got a large can of old coffee from Jeremy, and my soda can. The coffee can wasn’t made of metal, however, so we had to get a new one since metal is necessary to make sure the can doesn’t melt during the calorimetry. We decided that since the pH test looked similar enough we might just end up using the same amount of methoxide was before, but couldn’t really continue since Sarah had to first buy a soda can on her own time. We decided to do more research on calorimetry and learned that Jeremy already had an empty soda can. We took the two cans and decided to get to work cutting the two after school.

Next class, I think that with the right amount of research we will hopefully be able to make our methoxide and biodiesel using the kitchen oil. If it can be purified in that class too, then we will be ready to compare the energy efficiencies of our two biodiesels.

2/27/19:

Sarah and I plan to take the next step and finish our calorimeter. After school, Sarah cut the two cans to size, and now all that is left is to drill the holes in the right places, which hopefully won’t take too long. Once that is done, we plan to start testing the energy efficiency of the olive oil biodiesel with the calorimeter, and make the methoxide + batch of kitchen oil biodiesel.

We went to the i-lab and cut holes in the cans using a handheld drill and a clamp, having put a piece of thick wood into the can in order to give us something to brace the can on. After, we picked two thin metal rods from the i-lab, bicycle spokes, for us to insert into the holes and brace on the bigger can. For our tests, we did have to do them under the fume hood, and we used the clamps used during previous titration experiments to suspend the calorimeter above the beaker with the oil. We realized, however, that to clamp it in place, we would need to drill holes into the bigger can too, so we went, drilled the holes, and fixed the calorimeter. After that, we set Logger Pro up on my computer and got ready to measure the temperature changes. Unfortunately, our original tests didn’t work out because the oil didn’t catch fire, so we had the idea of placing a small candle under the dish of oil and heating it up. This wouldn’t work, but then Jeremy found a box of wicks in the storage room that we started testing on. Not even the wick worked, however, and we retreated for more research, eventually setting on dousing a paper towel in the oil and lighting it on fire. Burning a paper towel finally gave a result that worked, and we decided that this method would be used.

Next class, we hope to figure out measurements and make the biodiesel from the kitchen oil so that we can finish tests on the kitchen oil biodiesel, and definitely finish tests on the olive oil biodiesel.

3/4/19:

Today, Sarah and I are going to start our energy efficiency tests. Last class we finalized our method, so this class we want to start the tests. Since the paper is going to take some time to burn, we will make our batch of kitchen oil biodiesel in the spaces in between.

Jeremy came to us and said that in his research he found a method that involved soaking steel wool in our given volume of oil and comparing the burning to time to when steel wool was burnt alone. Sarah and I, after deliberation, decided that this would probably be more accurate than if we burnt paper, so tested it out. We realized that burning the steel wool alone would do nothing, since it doesn’t burn that way, so we set the oil up and started tests. Even then, steel wool didn’t work out, so we decided to go back to paper like before. This worked, and at the same time, Jeremy told us that his research had found that diluting the oil with water should allow us to perform the titration with little difficulty. In the end, we used baking soda to set the fire out by sprinkling the baking soda over the flame, and then letting the fire cool. At the same time, we made the methoxide while waiting for the fire to die down, so we didn’t waste time. The calorimeter did get a little charred and covered in black dust that we could brush off, which was pretty cool. The fire was also still pretty big, though under control under the fume hood because the entire dish worth of oil was burning. The last 2 times, however, baking soda wasn’t necessary because the oil and paper burnt out and then stopped. After, we cleaned up.

Next class, we plan to titrate and figure out the amount of methoxide needed for our kitchen oil biodiesel, and then make the batch and hopefully even clean it. We also want to calculate the calorie/energy change that happened with the olive oil biodiesel.

3/6/19:

Today, Sarah and I plan to titrate the kitchen oil and figure out its acidity and the amount of methoxide necessary, though I am wondering if we really need to titrate or if we cannot just use the same amount of methoxide. Time is now limited since we want to spend most of Friday on analyzing the data for the Data Analysis assignment and hopefully starting on the poster, meaning that we need to finish our tests today if anything.

We ultimately ended up deciding to perform the titration, with the worst-case scenario being that we finish testing on Friday and do data analysis on the weekend. It was surprisingly efficient, using our university article source to help us with the titration procedure. Sarah made the three analytes necessary, and I titrated them and recorded data. I did mess up one round, and end up putting too much in, so we had to do an extra. We even had enough time to clean up and mix the new methoxide batch up. This one had a different ratio of potassium hydroxide to methanol. We ended up staying behind after class for about ten minutes to mix the new methoxide and kitchen oil for ten minutes and then left them to separate.

After school, we plan to come and separate the glycerin from the biodiesel and purify it. This way, we can finish our energy efficiency tests the next class on Friday, and do the data analysis in the extra time.

3/8/19:

Today, Sarah and I are going to finish our tests with the kitchen oil biodiesel. Sarah went yesterday and purified the oil, so we are ready to burn it. Hopefully, we can finish the tests quickly and spend time on data analysis. We did figure out that we should have purified the kitchen oil before turning it to biodiesel because we ended up with a chunk of gross stuff in the biodiesel from the dirt in the kitchen oil that we had to take out, which was really nasty. The two different biodiesels were different colors, with the olive oil being more yellow and the kitchen oil being more orange.

Sadly, as our other tests started, the biodiesel that was recycled was not nearly as efficient as the pure olive oil biodiesel, a non-surprising yet disappointing fact. We also hypothesized that the recycled biodiesel was just not as flammable as we would have liked. The next round, however, we messed up and it didn’t even catch on fire, and the round after, we realized that our first recycled biodiesel test was wrong. The entire paper had been soaked in oil, so it wasn’t able to function properly as a wick and we didn’t get accurate results. The new test was done properly, and the entire oil caught on fire and burnt away like it was supposed to. Thankfully, our main three tests were done properly and we saw temperature/energy changes very similar to the pure biodiesel, which is what we hoped for. We finished everything and calculated the average energy change in calories and in joules. The pure biodiesel still released about 2x more energy than the recycled biodiesel, but both were decently efficient.

Next class, we will start working on the poster and finish data analysis, which we will start this weekend during our debate tournament.

3/11/19:

Sarah and I plan to start and hopefully finish the poster today.

We used the example presentation to create our own. Since the font was so small and odd, we created a new document with the information, and then copy pasted and edited to suit our needs. We finished rather quickly, though it was a pain to resize things.

Next class, we want to finish the poster and go over any edits.

3/13/19:

During our calculations, we realized that we messed up and that heat capacity in calculations was heat capacity of water and not oil, so our calculations were off and the Joules were much closer than we realized. Instead of being 2x more for the pure olive oil, it was hardly a difference of 1000 joules. We edited that, and thanks to the extra time, fixed the data analysis, table, and poster. It correlated our results better, in the end. We finished decently quickly, and since I had had an allergic reaction in the morning, unfortunately, it gave me time to rest a little.

References:

- https://www.luc.edu/media/lucedu/sustainability-new/pdfs-biodiesel/Biodiesel%20Curricula%20-%20Version%205.0.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

- https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2016/02/Fueling-Clean-Transportation-Future-full-report.pdf..

- http://www.uwosh.edu/faculty_staff/gutow/Chem_106_F07/Fuel%20values.pdf

- https://www.wikihow.com/Build-a-Calorimeter

- http://www.chem.tamu.edu/class/fyp/stone/tutorialnotefiles/thermo/thermo.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFpFCPTDv2w

Leave a comment