Planarian Memory Retention Post-Regeneration Research Paper

Introduction:

Planarians are often used as a “model organism” in neurological research specifically because of their regenerative properties (Creighton 2014). The planaria ability to asexually reproduce is due to high concentrations of stem cells in their bodies that enable them to regrow sections of their body. Planarians also have many adaptive features by using Wnt pathways to determine which portion of their body to regenerate (Lobo, Bean, & Levine 2012). For example, high levels of Wnt pathway activity at the wound indicates posterior development while low levels indicate anterior development. Studying Planarian regeneration could have huge impacts on future research in recovery as planaria are able to regenerate nearly every body part. This could also lead to advancements in limb and brain damage recovery, because hopefully, with more research and understanding of muscle memory related to limb regeneration, scientist will be able to facilitate regrowth of a replacement body part in humans, a trait humans are not born with (Zielins, Ransom, Leavitt, Longaker, & Wan 2016).

Past research has been done into memory in planaria post-regeneration through virtual conditioning—putting planarians through the same conditions repeatedly and testing if they exhibit the same response in those conditions when they regenerate. One experiment developed a computerized training and testing paradigm that would test planarian memory, and they found that the worms exhibit familiarity with their environment after amputation for at least a fortnight (Shomrat & Levin, 2013). Even further, they found that the tails that regenerate exhibit evidence of memory retrieval after gaining a new head by responding to the same conditioning the original planaria was put through. One experiment found that when put in a solution of ribonuclease, head fragments post-decapitation displayed similar memory of conditioning as non-amputated heads, but the tail fragments were a bit more variable(Corning & John, 1961). This leads to the belief that some memories may be stored outside of the head in planaria, though it is unconfirmed. Additionally, it was found that there are signs of the existence of a neural network in planaria, or a system of neurons spread throughout the body. This would lead to the idea that the neurons in the regenerated part of the planaria retain the same changes in cell structure as the original body pre-amputation (Aoki, Wake, Sasaki, & Agata, 2009). Even if the head was cut off, the body would keep the conditioned response from before. Evidence of memory stored in neural networks has not been found concretely, but one experiment exploring this was done by James McConnell who suggested memory in flatworms could be transferred through cannibalism (Duhaime-Ross, 2015). Widely known as “the cannibalism experiment,” the study tested another McConnell theory: that memory could be transferred chemically from one flatworm to another through something called “memory-RNA.” Memory-RNA, McConnell suggested, was a special form of RNA — the intermediary form of genetic information that fills the gap between DNA and proteins—that could store long-term memories outside the brain. McConnell fed bits of trained flatworms to untrained planarians. As a result, McConnell claimed, the untrained flatworms performed behaviors that the trained flatworms had previously learned (Duhaime-Ross, 2015). These experiments showed traces of memory retention but results were not definite. Scientists hope that the comparative ease of automated systems will lead to more planarian research, and their results suggest some trace of the memory stored in neural circuits outside the brain. Thus, this experiment would start to explore planarian memory vivo further through exploring habits and using repetition as a means to condition planarians—exploring memory retrieval through observing natural choices the planarians make.

Thus, we asked ourselves: Do planarian trunks and tails keep memory after both amputation and regeneration? There is high speculation that planaria will keep some memory after amputation and regeneration thanks to the studies that have found that some memories could be stored outside the head (Aoki, Wake, Sasaki, & Agata, 2009). A potential result of the experiment would be partial memory caused by neoblasts that are connected to a neural network or other outside memory storing functions not retaining all the memory causing the data for the conditioned tails to be worse than the heads. Another potential result could be that the conditioned planaria do better overall because most of the memory will be stored in the neural network. Possibly, the heads would do better than the tails because they would be better developed at the end of the two week regeneration period and thus better prepared for the maze. A distinct possibility is also that there is no correlation between the timings in the maze whatsoever and the group is left with no solid evidence as to whether planarians keep their memory post-amputation in the tail segments. Another factor could be that using a maze as the method of conditioning may not work for planarians. There are many probable outcomes to the experiment, especially since it will be done on live animals in a relatively short time frame. Overall, the experiment’s goal is to find if the conditioned tails can perform better than the unconditioned heads and tails.

Methods:

For the experiment, the planarians were first conditioned until they displayed retention, then they were amputated and tested after their regeneration. Two batches of twelve planarians were used in this experiment. All of the unconditioned and conditioned planarians were kept in their own wells in a dish and were all fed once at the same time in those ten days.

The independent variable in the experiment was the body section and the dependent variable was the planarians’ response to the same conditioning after their regeneration. To set the experiment up, a 24-well dish was filled with water, and six planaria were chosen for conditioning (Figure 3.) These planarians were kept in the same dark environment in spring water at at 21°C to 23°C. Twice or thrice a week, overall equaling a total of ten conditioning rounds, the planaria would be urged through the maze using light as a negative stimulus and their time recorded in a spreadsheet. At the end of ten rounds, all the planaria would be amputated, and the heads and tails kept in separate areas for a total of four sections: conditioned and unconditioned heads, and conditioned and unconditioned tails (Figure 3).

A maze was used for conditioning (Figure 1 & 2). The maze was 3D-Printed in the I-Lab and hot-glued into a petri dish to keep it still. The maze was a controlled variable used as a familiar environment for the conditioned planarians. A flash light was chosen as a stimulus to guide the planarians through the maze. Light was chosen as a stimulus specifically because planarians exhibit negative phototaxis— due to their sensitive eye spots— causing them to have a reflex-like reaction and moving towards the dark(Planaria). At the beginning of each conditioning session, the maze was rinsed with ethanol and clean water and dried, before being filled with fresh spring water. The planarian was placed at the beginning of the maze and guided through by the light shining behind the planarian and shading in front of the planarian as shown in figure 4. The time the planarians took to finish the maze was recorded each time. After the conditioning of six planarians ten times, all twelve planarians were amputated and given two weeks to regenerate fully. This was done on two batches of planaria.

After a fortnight for regeneration, during which a second batch would be put through the same procedure, a final testing round would be done and the time taken to get data for analysis. The dependent variable would be measured based on observations on whether it follows the same conditioned paths. The data for body section and conditioned versus unconditioned would be put into t-test to statistically analyze to see if there is a true correlation or difference. Thus we would test the memory of planaria post-regeneration of their conditioning.

One issue we encountered was that some planaria died during the conditioning process. There was no clear reason for this—one theory was that the planarians were hungry and so we fed both batches, which seemed to alleviate the problem for a time. The problem resumed although planaria are supposedly able to go a month without food. Another plausible reason was that conditioning for a long period of time could have caused stress in the planarian. Ultimately, the final testing times were done with less planaria than the group started with. The averages of each section thus were calculated with a different number of planaria, causing the data to be less precise.

Data:

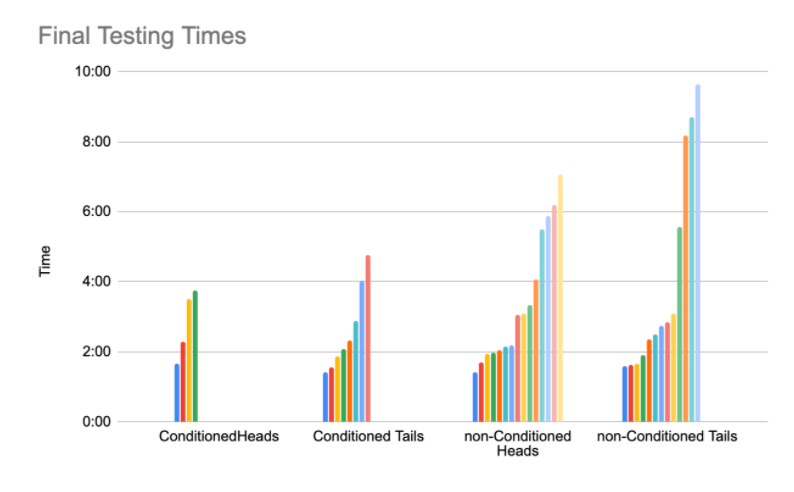

Figure 1: 12 days after conditioning the planaria through the maze, final testing times were recorded. The time on the y-axis indicates how long it took the planaria to complete the maze in minutes, ranging from less than two minutes to almost ten minutes. The x-axis represents the four different groups of planaria, with each bar in the section representing a different planaria that was tested.

Figure 2: The average times for each group from the final tests post amputation. The y-axis holds times in minutes, and the x-axis holds the average times for each of the four categories. This result does not correlate with Figure 1 due to misrepresentations of average times caused by many of the planaria dying, leading to certain averages being taken with four tested planaria and sixteen in another category.

Figure 3: Conditioned planaria versus non-conditioned planaria average times. The y-axis is in minutes and the x-axis is the two categories of planaria: conditioned and non-conditioned.

Figure 4: The average times of heads, both conditioned and unconditioned, versus tails, both conditioned and unconditioned. The y-axis is time in minutes, and the x-axis is the two categories of planaria.

Figure 5: Shown above are Batch 1’s timings over the training period organized by individual planaria. The y axis shows the time in minutes that it took the planarians to go through the maze. The x axis shows each round of conditioning (meaning each time they went through the maze). Each color represents a certain planarian and shows their progress over the ten rounds. Timings at the beginning and the end of the rounds were around the same. It was observed that although the times did not seem to show much improvement, the planarians were making the right turns just slower. It was hypothesized that the planarian gradually lost energy. Additionally, planarians were splitting during our conditioning period, so we had to remove their tail sections and condition their posterior end. For Batch two we tried to be more consistent with our conditioning and also kept the planarian in larger containers causing their death and splitting rate to be lower.

Figure 6: Shown above are Batch 2’s timings over the training period organized by individual planaria. Timings at the beginning and the end of the rounds were around the same. Even though the improvement over time was not significant and it seems like the first round showed the quickest reaction to light, the planarians still demonstrated that they have the potential to remember how the maze works and travel it quicker in the final test.

P-values

| Comparison | Excel T-value? | T-value calculation Online | P-value |

| Heads (trained vs not trained) | 0.8 | 0.26 | 0.8 |

| Tails (trained vs not trained) | 0.53 | -1.03 | 0.3 |

| Trained (heads vs tails) | 0.52 | -0.66 | 0.52 |

| Not trained (heads vs tails) | 0.21 | -1.69 | 0.109 |

| Trained tails vs not trained heads | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0.27 |

Results:

Based on figure 2, the non-conditioned heads did the best at 2:37, followed by the conditioned heads at 2:48, the conditioned tails at 3:26, and the non-conditioned tails at 4:02 on average. The timing gap between the heads and tails is larger at 2:40 for the heads and 3:43 for the tails, supporting one of the potential hypotheses made that the heads would do better than the tails. Excluding the difference between the heads and tails, Figure 3 shows that the conditioned planaria at 3:18 had a faster average time by 11 seconds when compared to the non-conditioned planaria at 3:29, though it is a relatively small margin. Furthermore, all raw data such as the timings for the two batches during conditioning and the final testing timings without taking averages can be found in Figures 1, 5, and 6. The raw data shows some variation between the four data sets (non-conditioned heads and tails and conditioned heads and tails), however, the high p-values shows that there is not enough significance between the groups to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, the statistical data rejects our alternative hypothesis: that the conditioned planarians will move faster through the maze than the unconditioned planarian.

Although the p-values suggest that there is not a difference between the planarians we trained and did not train, there is still a possibility that planarians are able to retain their memory post amputations. Problems and inconsistency during the experiment had a lot of impact on how precise the data turned out to be and many of the averages taken from the final testing timings ended up skewed due to planarian death and spontaneous splitting during the two week regeneration period, possibly because of the experimental design and stress caused conditioning through the maze. Therefore, the amount of data varied, making the data less consistent. As seen in Figure 1, the conditioned heads had the most deaths, followed by conditioned tails, then non-conditioned tails, and finally non-conditioned heads. During the final evaluations, some batches such as the conditioned heads only had four planaria for testing while others, such as the non-conditioned tails, had more than sixteen. Thus, the p-values show that while there’s not enough significant difference between conditioned and non-conditioned planaria, the amount of data and the duration of the conditioning is not enough to either reject or prove the hypothesis.

Discussion:

The overall data neither supports nor disproves the hypothesis that the conditioned planaria were faster in the maze than the non-conditioned planaria; more experiments would have to be done to come to a more robust conclusion. Though the conditioned batch did better than the non-conditioned batch on average (Figure 3), a look at specific averages for conditioned heads, conditioned tails, non-conditioned heads, and non-conditioned tails tells a different story, as the non-conditioned heads were actually the fastest batch on their own (Figure 2). This is an odd result because when looking at raw data, it appears that conditioned heads did the best, followed by conditioned tails, and then the non-conditioned heads and tails (Figure 1). One reasoning for this discrepancy in the averages would be due to the fact that many planaria died post-amputation, and thus the averages for each category were taken from an unequal number of planaria, thus skewing them. This discrepancy is linked to the difference between the number of surviving heads and tails; only four conditioned heads survived, while fifteen conditioned tails survived. This phenomena is again most likely linked to the stress levels of the planaria. Because the planaria were usually quick in their first round, this could be an inconsistency between the unconditioned and conditioned groups. The unconditioned groups had not had the stress of conditioning, so they would be relatively fast during the final test, even though they had no memory of the maze. Additionally, the unconditioned groups have had less exposure to light before the experiment, potentially causing them to have a fast reaction during the experiment. However, this could also be linked to the fact that with only ten rounds of training the planaria, it is unsure whether they were fully conditioned in the first place. If they were not, then it would be impossible to find results at the end as far as retaining memory went.

In the future, an improvement to this experiment would involve conditioning the planaria without the risk of killing them due to stress. We theorize that this would take a longer time, as a larger gap would be necessary between the rounds so they have a break, and more conditioning rounds. More conditioning rounds would be necessary in this case to make sure the planaria adapt to conditioning and don’t lose memory during the larger gaps. These larger gaps in between rounds, adjusted for with more conditioning than ten rounds, would mean that the planaria have enough time to adapt to the conditioning without getting stressed out and dying. Building on the findings of the experiment, it would also be possible to explore the memory retention of planaria in not only heads and tails, as we did in this experiment, but in heads, trunks, and tails. A second experiment would be to change the method of conditioning to feeding the planaria at set times during the day no matter what, until they moved to that area of their habitat regardless of the presence of food or not (Planarian). The overall experiment had a large margin for error—human error in conditioning, taking down timings, amputation, feeding times, and the number of planaria that survived all impacted the results. This method of conditioning would take considerably more work and precision compared to the maze method, but would not stress the planaria out, thus reducing their chances of dying considerably. During the final test, shining the light on the whole maze instead of providing shade could’ve been a more effective method, forcing the planarian to make their own decisions. Overall, we saw that even the conditioned heads were stressed under the light and could not navigate all the way through, so we provided shade and recorded the timing instead. Additional conditioning may have helped them go through quicker without guidance which would show us a more significant gap between the conditioned versus the unconditioned—since the unconditioned planarian would not follow shade and the planarians would rely on their decisions.

Experimental Set-Up

Materials:

- 2 24-well dishes

- 4 6-well dishes

- 1 large petri dish

- Spring water

- Planaria

- 3-D printed maze

- Timer

- Flashlight/lamp

- Magnifying Glass

- Knives

- Sterilization Material

- Micropipettes

- Beakers/Flasks

Procedures:

Protocol for Planaria Transfer:

- Fill half the wells in the 24-well petri dish with 1.5 mL of water.

- Cut off the end of a pipette with a pair of sterilized scissors.

- Transfer the planaria carefully into the wells, one planaria per well.

- Of the twelve filled wells, six should contain planaria for conditioning and six should be the control group.

Protocol for the Care of Planaria:

- Check on planaria using a magnifying glass.

- Replace the old spring water in the 24-well dish: 1.5 mL fresh spring water in each well daily.

- Keep one planaria in each well of the dish.

- Make sure that each planaria goes back to its correct dish.

Protocol for Conditioning:

- Make sure you are in a dark room.

- Cover the end of the maze in aluminium foil for darkness

- Place the maze into the petri dish.

- Fill the maze with water.

- Start the flashlight and place it at the beginning of the maze.

- Place the planaria at the beginning of the maze and start the timer.

- As the planaria moves away from the light of the flashlight, guide the planaria with shadow using tin foil order to nudge it along. Keep its head in the dark, but it’s body in the light.

- Once the planaria reaches the dark end of the maze turn off the timer and record the time.

- Repeat steps 5-7 for all the planaria in the conditioning batch.

Protocol for Amputation:

- Put gloves on.

- Sterilize the entire area around you with liquid ethanol.

- Sterilize the knife and hands with liquid ethanol.

- Take one planaria out of its dish and onto the sterilized amputation surface.

- Slice in half.

- Keep the head segment in one well and the tail segment in a second well.

- Repeat 4-6 for every single planaria, and keep conditioned and non-conditioned planaria separate.

Protocol for the Testing of Planaria:

- Make a spreadsheet with 4 sections for recording data: conditioned heads, conditioned tails, non-conditioned heads, and non-conditioned tails.

- Fill the large petri dish with spring water.

- Place the maze into the petri dish.

- Cover the end of the maze for darkness

- Start the flashlight and place it at the beginning of the maze.

- Place the planaria at the beginning of the maze and start the timer.

- As the planaria moves away from the light of the flashlight, follow the planaria in order to nudge it along.

- Once the planaria reaches the dark end of the maze turn off the timer and record the time.

- Repeat steps 6-8 for each planaria from each batch and record all the information, especially the timing

Daily Reflections

1/22/20 – Wednesday:

- Finished and Submitted Group Declaration

- Did more brainstorming

- Created the shared group folder

- Made the contact document

- Made the experimental notebook

- Made a schedule for conditioning, amputation, and testing

1/24/20 – Friday:

- Finished the schedule from last class

- Wrote down protocols

- Made an images document to start logging images down

- Decided to use a 24 well dish, which was then labelled

- Drafted learning objectives for the future

- Set up a spreadsheet for the results and data from the experiment

1/27/20 – Monday:

- Set up the experimental notebook for another protocol

- Re-printed the maze because the first attempt had an error

- Set up the dish for the care of the planaria with 1.5 mL of spring water in each well

- Transferred the planaria into their new homes

- Did trial runs of the conditioning in order to determine approximately how much time each run takes.

- After school, the first round of conditioning was run on the planaria.

1/29/20 – Wednesday:

- Yesterday, the second round of conditioning wasn’t completed, so two rounds of conditioning were planned for today.

- We were confused because it looked as though some of the planaria had amputated themselves, or there were suddenly extra planaria, so we examined them under a microscope.

- Realizing that they had ripped themselves up, and that this was natural, we took the tail segments out and kept conditioning the head segments

- We did a thorough check of the rest of the planaria then, just to affirm that they were all fine.

- A3 would not cooperate, and we decided to condition it later.

2/3/20 – Monday:

- We set up our schedule for the week for conditioning, knowing that we would be amputating the first batch at the end of the week

- We set up the second batch of planaria for their conditioning in a new dish

- The first batch were conditioned

- B3 and B5 split from Batch 1

- We started are putting the planaria in the dark right after they are conditioned so they get some “reward”

- We worked on the introduction section, to incorporate all of our notes/paragraphs into one rough draft.

- Before we could condition batch 2, A1, A3, and B4 escaped and died. We replaced those, then conditioned A1 and A2 in batch 2.

2/4/20 – Tuesday:

- Finished round 1 of batch 2

- Replaced B2 (batch 2) with new planaria before trial because it was inanimate

- We don’t need to work in the dark – everything is more clear and shading the maze is easier

- There was no planaria A4 so we replaced it

- A4 was accidentally conditioned

2/5/20 – Wednesday:

- A1 and B2 both escaped from their water and died in Batch 2

- We realized that they were committing planaria suicide by escaping from the water

- Thinking they might be hungry, all of Batch 2 was fed ground beef liver

- We took A4, which was accidentally conditioned, and put it in place of A1, which had two rounds of previous conditioning

- Took the dead planaria out and disposed of them

- Replaced the dead planaria

- Finished drafting the learning objectives and submitted it.

- Came after school to complete the conditioning of the planaria

- B5 from Batch 2 split up, and since he is a non-conditioned planaria the tail segment was just removed

2/6/20 – Thursday:

- Conditioning at lunch did not work out because none of the planaria would cooperate, and so it was put off until the end of the day

- In Batch 1, B4 moved into B2, and since one of them is non conditioned, it was decided to condition both for Round 10 and during testing, take the longer time out

- A new planaria was put in B4

- A3, A4, and B3 of Batch 2 split, and so the tail fragments were taken out

- Everyone was a bit frustrated with what was happening because of how much they split

- We finished conditioning in the afternoon of Round 10 for batch 1, so that the next day we would be ready to amputate.

2/7/20 – Friday:

- We came in at lunch today

- Changed out the old water for freshwater for both batches

- Amputated all the planaria in Batch 1 and kept the heads and tails separate

- Heads stayed in the original environment, tails were moved down to a new home

- A1 tail went to C1, B2 tail went to D2, etc

- B4 and B6 in Class 2 split, though both were non-conditioned

- Finished conditioning for B1 and B2 in Batch 2 for their Round 3

- Officially started the 14 days of regeneration time that the planaria in Round 1 get

- B3 wouldn’t cooperate in Batch 2, so we put it off until later.

2/10/20 – Monday:

- Round 6 of conditioning + catch-up for B3 in Batch 2 was done

- C6 from Batch 1 split even after the splitting on Friday

- A3, C3, C6, and D4 all split in Batch 1

- A2 and A5 died somehow in Batch 1, and one was conditioned

- C6 has split (one has a head with no tail)

- B3 was missing in Batch 1, and could not be found.

- A1 in Batch 2 has a tendency to loop around in the same area a lot.

- We set up the conditioning schedule for the week so that we could split on Friday

- In Batch 1, we originally thought that B3 had moved into A2, and we moved him back, but it turned out that A2 in fact split and that B3 committed suicide.

- We ended up putting a new planaria in the B3 and conditioning him again

2/11/20 – Tuesday:

- Round 7 of conditioning was done at lunch.

- B3 from Batch 2 split into two heads somehow

- The bigger B3 split again during conditioning, and we threw away the tail segment

- One of the B3s was put into C3 but his conditioning continued since it was unsure which one was the original.

2/12/20 – Wednesday:

- Today we finished B3 Round 8 of conditioning and did Round 9 of conditioning for Batch 2

- Nothing was wrong with the planaria this time, thank god, so we jumped right into conditioning.

- The water for Batch 1 and Batch 2 was replaced so that it would be clean

- Batch 1 was fed so that the basic conditions of the different batches would be identical, each having been fed once.

- B3 was noticed as continuing to turn the exact same way every single turn no matter what, and as such, at the same final turn during conditioning, it would turn the wrong way and loop in that area.

- Prepared to do Round 10 of conditioning on Thursday, and amputate on Friday

2/14/20 – Friday:

- It’s Valentines Day!

- We did Round 10 of conditioning for Batch 2 of the Planaria

- In preparation for February Break, we refreshed the water for both batches

- All 10 rounds of conditioning done, we also amputated Batch 2

- B1 Batch 2 Split, so we took the tail section out and kept conditioning

- A canvas of the Batch 1 told us that:

- A3, B2, and C4 were all missing, presumed dead

- A2, A5 were confirmed dead

- D2 and A2 were confirmed to have split sometime in the past few days

- Overall, Batch 1 was a disaster, and we made a new sheet in our Data spreadsheet to keep track of what had happened by day

- We ended up transferring Batch 2 Planaria into 4 6 well dishes, one for each type, because we thought that maybe with more space and water the planaria wouldn’t go feral over the break and keep splitting themselves or dying.

- There was a lot of work on the spreadsheet to set it up for testing and to mark the contents of the different dishes and the planaria in them.

- C3 who was being conditioned also ended up with his own little home

2/24/20 – Monday:

- We took detailed notes on the contents of our different dishes and how many planaria were in each.

- Some planaria split and some died, but overall the average number we would get from each batch would remain the same

- It was also time for testing the Batch 1 now that the regeneration for that Batch was complete, so we started testing the planaria in Batch 1

- It was a bit problematic at some points because the planaria would be dead, but the overall average should work out.

- We went over the feedback given by Jehnna on our learning objectives and fixed that document

- Next class we will finish the Batch 1 test timings

2/26/20 – Wednesday:

- Today was the learning objectives check in, so we did a quick review of those together before having our conversation with Jehnna about the background research

- The conversation went well—we discussed how planaria regenerate, different stimuli for conditioning, and what the experiments indicate.

- We switched out the water for both Batches, and checked that nothing had changed since Monday.

- C4, one of the planaria we needed to test, still wasn’t done regenerating and didn’t even have eyes, so we put its testing off until next week.

- We finished testing Batch 1 planaria, officially done with that batch, and thus ready to test batch 2 next week.

- Neither C6 or D6 were cooperating, so we put them off until next class.

3/2/20 – Monday:

- A lot of conditioned heads died over the weekend, but luckily none of the conditioned tails died in Batch 2

- We changed the water out for all of Batch 2 and started testing their timings for our final results post-conditioning

- We also delegated work for the upcoming STEM Fair by figuring out how the graphical abstract and the report paper would be done.

- Worked on both the report paper and the graphical abstract

- Finished all testing for Batch 2 conditioned, and the two extra planaria from Batch 1 that would not cooperate last Wednesday.

3/6/20 – Friday:

- We finished testing the non-conditioned planaria as a group

- Hope worked on the graphical abstract on Canva

- Nikki finished up the Introduction Section and the Methods section.

- Work was pretty much moving into a section where we worked more on the report notes than on the experiment, since we were finishing up testing.

3/9/20 – Monday:

- We worked more on the Report

References:

Aoki R., Wake H., Sasaki H., & Agata K. (2008). Recording and spectrum analysis of the planarian electroencephalogram. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306452208016655?via%3Dihub

Corning W.C. & John E.R. (1961, October 27). Effect of Ribonuclease on Retention of Conditioned Response in Regenerated Planarians. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/134/3487/1363

Daniel L., Wendy B., & Michael L. (2012, April 26) Modeling Planarian Regeneration: A Primer for Reverse Engineering the Worm. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002481#abstract0

Jay B. & Irvin R. (1962). Maze Learning and Associated Behavior in Planaria. Retrieved From https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1964-00492-001

Planarian. (2019, December 15). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planarian

Planarian Care Instructions: Psychology: George Fox University. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.georgefox.edu/academics/undergrad/departments/psychology/ckoch/research/plancare.html

Planaria: Psychology: George Fox University. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.georgefox.edu/academics/undergrad/departments/psychology/ckoch/research/planimal.html

Planarians, Regenerations, and the Medicine of Future: Jolene Creighton. (2014, September 20). Retrieved From https://futurism.com/neoscope/planarians-regeneration-medicine-future

Shomrat T. & Levin M. (2013) An automated training paradigm reveals long-term memory in planarians and its persistence through head regeneration. https://jeb.biologists.org/content/216/20/3799

Using Planarian Flatworms to Understand Organ Regeneration. (2012, October 25). Retrieved from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-10-planarian-flatworms-regeneration.html

Duhaime-Ross, A. (2015, March 18). Memory in the flesh: a radical 1950’s scientist suggested memories could survive outside the brain—and he may have been right. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2015/3/18/8225321/memory-research-flatworm-cannibalism-james-mcconnell-michael-levin.

Neil D, Mack C, & Michelle E. (2018, November 9). “Behavioral Research with Planaria.” Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6701699/

Leave a comment