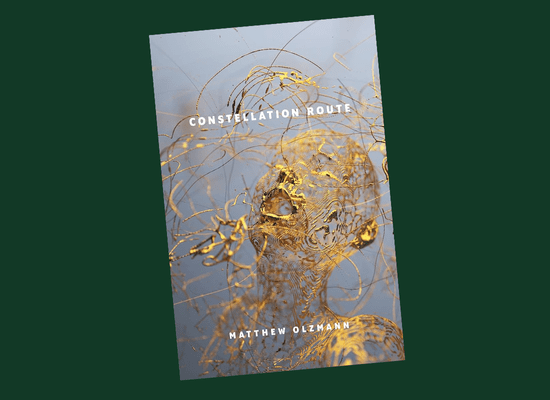

Constellation Route, by Matthew Olzmann, is a collection of poetry concerning politics, relationships, mythology/history, fate, and time. Olzmann has a casual, modern style of writing his poetry that makes heavy topics feel conversational, and draws upon his background in improv to add meaning and rhythm to his poems. He draws heavily upon humor and pop culture references to discuss heavy topics about American politics, but not in a way that feels preachy. This collection of letters is also particularly unique because he formats most of it in the form of letters to different people, going through the US Postal Service.

Political themes enshroud the entirety of Olzmann’s book—they are inescapable and inextricably linked to the form of his poems. The very first poem reveals his disillusionment with American politics: “A good place to hide a sociopath is a full-length mirror. / A good place to hide that mirror is the heart of America” (Letter to Bruce Wayne, 6). He continues in the poem to discuss how in Gotham City, at least their villains are obvious—Joker with his obvious gimmick, for example—but in the real world we all have villainy in us, hidden away. He discusses gun violence in couplets, the form of the couplets feeling almost like bullets on their own in how short and pointed they are: “A bullet doesn’t care / about aim, it doesn’t / distinguish between / the innocent and the innocent” (Letter Beginning with Two Lines by Czelaw Milosz, 24). He even discusses racial politics in a poem about how his wife wants him to introduce them and mention that she is black for her own safety: “She wants me to mention it will be safer for her this way, / safer than if she were to ring your doorbell / and introduce herself, by herself” (Letter to my Future Neighbors, 51). The poems together paint a grim picture, but the topics are handled meaningfully, each poem unique and well-formatted to suit the topic. In “Letter to Bruce Wayne,” the reader does not even realize that it is necessarily about politics until most of the way through the poem, and by then, you are already drawn in.

Olzmann’s discussion of politics links closely to his usage of pop culture and what pop culture teaches us about ourselves. He uses Gotham City as a foil to America: “But here is Gotham City and I’ve been / so naive: believing the truth of the old mythologies. / How they promised a recognizable villain, / a clown with a ruby-slashed mouth, a lunatic’s laugh” (Letter to Bruce Wayne, 6). Olzmann’s point is that villains are not recognizable, that they are not obvious like in Gotham and in comic books, despite how much we would like it that way. He discusses wanting to escape from this universe and the heaviness of its politics—a message that rings truer than ever with the wars in Ukraine and Gaza—when he writes that “There are hundreds of reasons like this / to long to be from some other galaxy, / century, or dimension” (Letter Written While Waiting In Line at Comic Con, 10). His poem titles further mirror how Olzmann can write a poem about anything, even standing in line somewhere, and still make it and his musings meaningful.

Olzmann does not stop at just discussing politics, however, but goes further and asks his readers: what can we do to make a difference in this world? He not only sets up the problem, but looks for solutions in open-ended, thought-provoking poems. For example, when discussing the environment, he asks: “Do you ever worry that because your voice is impossible to hear, maybe no one will make the effort? That you can work really hard and try to be a good person and try to make a difference in your community, but then—at the end of the day—the waves will just swallow you whole?” (Fourteen Letters to a 52-Hertz Whale, 43). This multi-section prose poem discusses a topic many grapple with: whether their individual efforts will make a difference. Olzmann doesn’t have an answer, but he pushes readers to think about it, and that is the most important part. He does not shove a message into your mouth; he asks you to truly think about it. That is what good poetry does; it provokes thought. He even discusses his own difficulties with doing good. He writes, “There are moments when compassion is a yes / or no question. We can donate our organs / to strangers or be buried with all our worldly possessions. / We can save the drowning man, or just think about it. / Sometimes there can be no hesitation. / And then I hesitate” (Letter to a Man Drowning in a Folktale, 55). Is he a bad person for hesitating? Or his he simply human like the rest of us, grappling with a hard choice that should be simple in practice?

Olzmann further uses religious and mythological language to discuss the burdens the world places on us. Linking closely to the last poem, he says, “I won’t die for anyone / not the way religion has taught me” (Letter to Matthew Olzmann from Cathy Linh Che on Saintliness, 16). It is sympathetic to be exhausted from fighting all the time, from trying to do good when the world seems to beat you down. He writes, “One weary seraph, malfunctioning and tired / from the long fight against gravity and malevolence. / His wings. They’re removable. Designed to be / unloosed when the burden of flight exceeds / the desire for flight” (Wing Case, 77). It is okay to get tired, to put down the burden for some time, to take your wings off, as it were.

Throughout the whole book, apart from difficult topics above, he uses the frameworks of history and time to ask about the impact we make on the world around us. He asks large, ponderous questions that do not have an answer but reflect the confusion he deals with in this book. He writes: “Fate makes an animal of us all, and rides us / through the village at sunrise where we are judged. / But we designed those villages” (Letter to the Horse You Rode In On, 8). So much of human judgement is self imposed, and he points it out. He discusses climate change, and how it will change the world around us ; “We still had the night sky back then, / and like our ancestors, we admired / its illuminated doodles / of scorpion outlines and upside-down ladles” (Letter to Someone Living Fifty Years From Now, 100). In this poem, the sky is completely blotted out from pollution, and it evokes a sense of nostalgia for history long gone. He draws upon a similar feeling in another poem: “History / is an ash-whitened field, / a twenty-square-mile arc of unremarkable flatness / in a space where some ancient breathing things / once stood (the way I now stand), their limbs / stretching to feel the wind weave / through their branches and fingers” (Letter to the Oldest Living Longleaf Pine in North America, 17). The world changes so much, and the nostalgia for times long gone or that we will never seen are not even political, but simply wistful. How much has the oldest pine tree seen? Humans are short-lived in comparison, and can hardly experience as much. It’s beautiful, and sad, and wonderful, all at the same time.

Constellation Route is ultimately a series of letters asking the world, what impact do we make? Is it our job to do better? What if we cannot? Who are we, as we walk the grand route of the universe? Themes of fate, history, and politics are wrapped in language of pop culture, religion, and mythology, all in Olzmann’s unique, casual diction. In the future, I want to try and write poems similar to Olzmann’s rhythmic yet casual style; he makes low-brow diction feel incredibly fancy, somehow.

Leave a comment