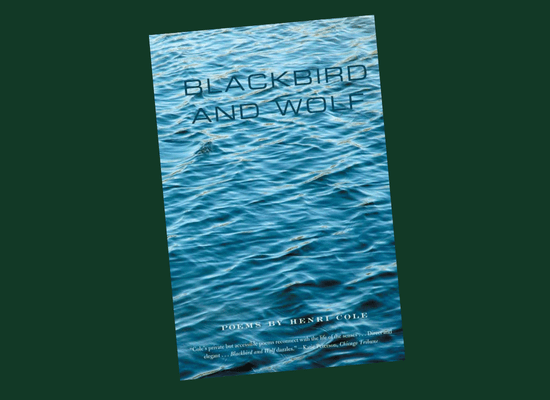

Blackbird and Wolf, by Henri Cole, is a collection of poetry about memory, love, and nature. Cole, a lover of sonnets, writes almost entirely in untraditional, unrhymed sonnets in his novel, with sharp turns into metaphors about nature that while at first glance seem unrelated to the topic at hand, reveal deeper meaning to his poetry. His strong imagery and masterful grasp of the English language create a book that will stick with readers long after it is over. He further is a master of sonnets, with almost every poem in the book being a sonnet or a version of a crown of sonnets. The short, strict structure of sonnets means that though he jumps around a bit in his poetry, every single line is laden with meaning, and no space is wasted. It requires you to read and reread poems to truly understand what is happening, creating a rich experience where the first read is not the same as the second or even the third.

Cole sprinkles his book with metaphors about nature, humanizing animals and plants as ways of discovering his own feelings. For example, he writes “summer spreads out, relieving the general, / indiscriminate gray, like a mouthful of gin / spreading out through the capillaries / of my brain” (Haircut, 30). His metaphors about summer turn into metaphors about his brain, one of the cleaner pieces of imagery. His writing often turns a little gruesome; in “Beach Walk”, he writes, “I found a baby shark on the beach. / Seagulls had eaten his eyes. His throat was bleeding. / Lying on the shell and sand, he looked smaller than he was. / The ocean had scraped his insides clean” (Beach Walk, 41). His nature imagery extends into personification, with talking animals taking the place of his internal monologue: ““Hey, human, my heart feels bad,” / a crow asserts” (Chenin Blanc, 9). All of this lends itself to the lightly surrealist experience of Cole’s poetry.

This nature extends into writing where Cole literally puts himself into the body of various animals and speaks from their perspective. It brings a raw realness to what he is feeling, and strips it from traditional human notions of emotion. For example, he writes “The world of instinct, crying out at night / (its grief so human), frightened me, / so I scribbled vainly, contemplating the surface / of the water, frolicking in it until my long, / amphibious body…” (Maple Leaves Forever, 10). He writes about wanting to escape his emotions using black bears as an example: “Shaking the apple boughs / he is stronger than I am / and seems so free of passion— / no fear no pain, no tenderness. I want to be that” (Twilight, 13). One of my favorite lines in the book is thus: “I feel like an animal that has found a place. / This is my burrow, my nest, my attempt / to say, I exist” (Embers, 37). Cole’s use of animal metaphors as he attempts to define his place in the world creates raw lines of emotions that truly encompass the human experience of self definition

Cole ventures into exploring topics around mental health and self definition through his poetry as well. With lines such as “By now, / I think I have been / entirely erased” (The Erasers, 16) and “Though the door is locked, I am free. / Like an outdated map, my borders are changing” (Birthday, 20), we see Cole change throughout the course of the book and with his poetry. His poetry is raw, almost a way of sacrificing himself to his readers—“At times, my life seems merely a root left behind for others / sampling my fruit, scooping the flesh out” (Persimmon Tree, 50). It is here that the titles of his poems begin to make sense; with the shortened sonnet structure, the titles help give his poems definition. They tell readers what he is thinking about when writing the poem. For example, the phrase “I’m competitive, / I’m afraid, I’m isolated, I’m bright. / Can you tell me how to survive?” comes from a poem called “My Weed,” which might seem humorous at first, but at second glance, reveals how he is looking to nature as he discovers himself (My Weed, 35). Just as weeds strangle out other plants to survive, so too is Cole competitive and surviving. He sees himself in the weed. Without the title, such self definition would not be possible.

Blackbird and Wolf is full of surrealist metaphors, tight sonnets, and confusing poems that skip around and yet somehow strike directly at the hearts of readers. Some of my favorite lines include “I’m sorry I cannot save I love you when you say / you love me. The words, like moist fingers, / appear before me full of promise but then run away” (Gravity and Center, 25), which is incredibly relatable to me, and “nature beats them apart, / putting their whole lives into the small sting / that hurts us, but not before changing gum / into gold, like poetry, which is stronger / than I am and makes me do what it wants” (Dune 58)—the very last poem in the book, cheekily self referential to the fact that Cole is letting the poetry guide him. His mastery of sonnet is to be lauded; I too hope to write tight sonnets such as Cole’s, with metaphors that strike at my heart.

Leave a comment