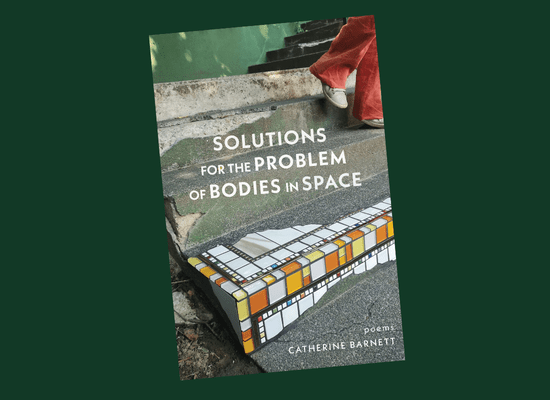

Solutions for the Problem of Bodies in Space, by Catherine Barnett, is an excellent book of poetry that tackles themes of loneliness, the body, art, and connection. She also uses prose to her advantage in the book, wielding it as its own individual form and as a form of poetry. The book is structured in three segments, with a series of prose poems, “Studies in Loneliness,” spread across the book in ten parts. Loneliness becomes one of the main themes of the book, present not just in that series but in many of the other poems, as Barnett reckons with the death of her father, among other things. The final poem even references the book’s title: “I had wished aloud for a solution for the problem of bodies in space, wanting to be in two places at the same time” (Studies in Loneliness x, 79).

Barnett’s exploration of loneliness as a concept is fascinating because being published recently, in 2024, it is in conversation with the loneliness brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, and as such, taps into global feelings about loneliness and the evolution of our idea of loneliness over the pandemic. In the very first poem, she asks “when did loneliness become equal parts strategy, ministration, origin story, addiction?” (Studies in Loneliness i, 5). Loneliness is hard to define—sadness, isolation, a loss of connection—but what does it mean in a world that is becoming more and more isolated and individualistic, and where more people take solace in loneliness? Barnett even states “I take issue with all the studies saying beware loneliness, avoid loneliness, it will speed your death. / I say it will speed your death only if you believe it’s a toxin” (Studies in Loneliness iii, 21). It is true that many people, especially neurodivergent people, found comfort in the isolation of COVID-19, as it gave them time to become familiar with themselves outside of the strict restrictions of society and work. Remote work became a norm, and despite the fact that going back into office would mean more human connection, no one wants to, and companies have to force it. How does loneliness fuel us? Barnett says that “some of us write to appease the loneliness, why else leave a mark? / I was here, words say, this is what it was like, don’t forget” (Studies in Loneliness iv, 35). I find that to be a very poignant and gorgeous idea, that loneliness can fuel artists and writers to leave a mark, to blaze so bright that they will be remembered long after their deaths.

She also quotes Beckett when saying “we are alone. We cannot know and we cannot be known,” and while this is true to an extent, human connection is all about becoming more known, and trusting people to know hidden parts of you. (Studies in Loneliness vi, 47). In conversation with her ideas on loneliness, Barnett talks about human connection as something to be learned and practiced, as socializing something that might not come naturally, but be a science. This idea resonates deeply with me, since social interactions do not always come naturally to me, and I loved her quote “the science of love, which is to start with objects—a tree, a rock, a cloud—and learn to love each one before trying to love a human being” (Studies in Loneliness i, 6). I think most importantly is that we learn to love ourselves before we learn to love anyone else, or that love will never be whole. Barnett also reckons with the loss of connection left by death, in her case specifically in reference to her father, though for readers, it could be any death: “the emptiness left by a death / is another species of loneliness / altogether” (Still Life, 39-40). Many people lost family during COVID, and Barnett asks us how we grieve when one of our connections is gone and we are still isolated. Is it easier, or harder? Barnett seems to process by writing poetry: almost the entire first section of the book dwells on specific memories she had with her father before his death, humanizing him with small touches like how he drove, or his love for martinis (Itinerary, 15). I think that this makes her father, or any dead, seem far more real than an imaginary concept.

Another strong theme running through the book is the idea of the body, specifically connection to our body and how we connect to it. She starts all the way at birth stating: “The doctors snip the cord. I don’t know if that’s when it starts” (Studies in Loneliness ii, 14) in reference to the origin of her loneliness. There are two veins running through the book: one of understanding the body after it is gone and the person is dead, and the other in understanding our own bodies when we are alive. For the latter she says “I keep buying secondhand cashmere sweaters because wearing cashmere makes me feel as if I’m wearing another human body”—a fascinating method of connecting with others (Studies in Loneliness ix, 72). For the former, she mainly references her father, stating “before my father’s hand was no longer my father’s hand” (Hyacinth, 20) and “The body is a big dumb object, he taught us. / Death is a genius” (Night Watch, 18). To a certain extent, our body is only a temporary possession; we are gifted it when we are born, and lose it when we die, but the actual components of our body belong to no one but death, and our existence belongs only to those who remember us. This seems a lonely concept until you remember Barnett’s statement that this fuels us to create, to make a mark, and then seems more curious than anything.

One of the most fascinating concepts in Barnett’s book was the way she wrote poetry in conversation with different art pieces. My favorite was her poem in conversation with Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s exhibit Infinity Mirrored Room, which I had the privilege of experiencing this summer at SF MOMA. She writes “I saw myself repeated into infinity, / which is different from the task at hand, / which is to accept finitude” (Art History, 37), and htis truly does capture the experience of the exhibit to an extent, the mind-bending nature of being in a box of mirrors where your reflection is the only thing you can see. The other main piece of art she reckons with was Tsukimi Ayano’s Village of Dolls, a village of life sized dolls the artist creates to populate her small village, mainly baked on people who have died or left. Barnett quotes the artist, saying ““I don’t think dying is scary,” the artist says. / “I’ll probably live forever.”” (Village of Dolls ii, 54). To a certain extent it is true, and reflects Barnett’s idea of writing to appease loneliness: the dolls represent the people who are gone, but the dolls, the art, will outlive them, the same way Barnett’s art will outlive her. In general, Barnett views art to be timeless: “paints look backward / and forward at the same time” (Untitled, 27), which is true, considering how we connect to art decades after the artists are gone.

Catherine Barnett’s Solutions for the Problem of Bodies in Space does an excellent job of reckoning with topics like loneliness, the body, art, and connection. While Barnett herself ultimately soothes her loneliness and finds purpose in creating art which will outlive her, her poetry also challenges readers to figure out their own solution to loneliness, and their own methods of creating human connection in a way that will outlive them. Barnett is very aware of the mortality of humans and our limited time, writing “sometimes the clock starts beating inside my heart, and then there’s even more noise, mortal noise” (Studies in Loneliness vii, 59), but it makes her all the more determined to try and capture the human experience in her poetry. Ultimately, it is an excellent book that I really connected to personally, and I want to try writing my own prose poems in the future and take inspiration from her.

Leave a comment